BLOG

The value of accurate fire was recognized in the 17 th and early 18 th centuries when period drill books recommended at least some target practice for British troops. In peacetime however, parsimonious issues of lead made practice with live ammunition difficult. Historian J. A. Houlding found that the government did not stint on gunpowder and flints but issued only 1 cwt. of shot to each battalion of foot annually. This worked out to about 2 to 4 musket balls per man per year. (Houlding p. 144) Instead of stressing marksmanship, peacetime training focused on the platoon exercise, firing blanks or “squibs.” In 1751 the Lt. Colonel of the 8 th Regiment of Foot stated that he wished the troops, "were accustomed to take aim when they present, No Recruits want it more than ours, few of them having fired or even handled Fire Arms before enlisted; the Explanation of the word “present” in the manual exercise, is very different in my Opinion from what Men shou’d do when firing at an Ennemy, this gives them a Habit of doing it wrong, and I have room to believe that the Fire of our Men is not near so considerable as it would be, were any pains taken to make them good Marks men” (Houlding, p. 280) James Wolfe, speaking of his experiences in Scotland during and after the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745, pointed out the benefits of firing live ammunition in a 1755 letter, "Marks men are no where so necessary as in a mountainous country. Firing ball at objects teaches the soldiers to level incomparably, makes recruits steady and removes the foolish apprehension that seizes young soldiers when they first load their arms with bullets. We fire first singly, then by files, 1, 2, 3 or more, then by ranks, and lastly by platoons, and the soldiers see the effects of the shot, especially at a mark or upon the water. We shot obliquely, and in different situations or ground from heights downward and contrarywise." (Findlay p. 271) It was during wartime that the British soldier got his chance to practice marksmanship. During the French and Indian War, Lord Loudoun issued these orders to the newly raised 60 th Regiment of Foot: "They are then to fire at marks, and in order to qualify them for service of the woods, they are to be taught to load and fire, lyeing on the ground and kneeling." (Houlding p. 375) In the summer of 1757 (the fourth year of the French and Indian War), the Lt. Colonel of the 15 th Foot reported, "We have three field days every week…7 rounds of powder and ball each every man has fired about eighty four rounds, and now load and fire Ball with as much coolness and allacrity in all the different fireings as ever you saw them fire blank powder." (Houlding p. 280) General Jeffery Amherst ordered his army, in winter quarters in New York during the winter of 1758-59, to “practice their men at Firing Ball, so that every soldier may be accustomed to it.” (Houlding p. 366). In the months leading up to the outbreak of the American Revolution the British commander in North America, General Thomas Gage, ordered his Boston-based army to practice marksmanship. Historian Matthew Spring points out that Gage’s men practiced almost every day. Dr. Robert Honeyman witnessed this activity. Honeyman recorded: "I saw a regiment and the body of Marines, each by itself, firing at marks. A target being set up before each company the soldiers of the regiment stepped out singly, took aim and fired, and the firing was kept up in this manner by the whole regiment till they had all fired ten rounds." (Spring p. 81). Captain Frederick MacKenzie, of the 23 rd Regiment of Foot (Royal Welsh Fusiliers) took part in the live firings at Boston: "The regiments are frequently practiced at firing ball at marks. Six rounds per man at each time is usually allotted for this practice. As our regiment is quartered on a wharf which projects into the harbor, and there is very considerable range without any obstruction, we have fixed figures of men as large as life, made of thin boards, on small stages, which are anchored at a proper distance from the end of the wharf, at which the men fire. Objects afloat, which move up and down with the tide, are frequently pointed out for them to fire at, and Premiums are sometimes given for the best shots, by which means some of our men have become excellent Marksmen." (MacKenzie p. 4) General William Howe, who succeeded Gage as Commander in Chief, also advocated the value of aimed fire, "The commanding officers of corps to practice their Recruits and Drafts in firing at marks, and may, when they think it necessary, order the whole out for that purpose." (Howe/Kemble p. 298). Thomas Simes, author of a 1768 military dictionary, suggested that new recruits should be taught to fire “with ball at the target till they can hit the object six times out of twelve, for without firing at a mark, men will not be marksmen; and without being sure to kill, soldiers are not in the best possible state of war.” (Simes p. 177). A decade later Bennett Cuthbertson advised, "When a convenient place can be obtained for fixing up a butt (a barrel), the Companies should perform all the different firings with ball cartridges once a month, it being the true method of training soldiers to the use of arms, and forming them for whatever service they may be called to; and in order to raise an emulation in this essential part of discipline, that Company, which in the course of a day’s performance, drives the greatest number of balls each should be distinguished until the next monthly practice, by a little tuft of scarlet worsted worn above the cockade." (Cuthbertson pp. 171-172). So we see it was customary during wartime for British soldiers to shoot at targets of various sorts to improve marksmanship. Such was also the case at Fort Niagara. Although recorded during peacetime, Captain Glasier’s Orderly Book from the 2 nd Battalion, 60 th Regiment of Foot documents several days of target training at Fort Niagara during March and April 1772. An entry for March 27 orders “Captain Stevenson’s Company to parade Tomorrow afternoon at 3 O’Clock for the Targate firing, all the men that is here of Captain Glasiers Company is to join Captain Stevenson’s.” Four days later Captain Hutcheson’s Company of the same battalion was ordered to parade for target firing. Training proceeded fairly regularly through April 1772. Another reference to shooting at marks comes in 1780 as Fort Niagara’s commandant, Lt. Col. Mason Bolton wrote to Governor Frederick Haldimand, “The Colonel has had his men [Butler’s Rangers] out this spring (or rather winter) frequently firing at marks, &c, &c. agreeable to your Excellency’s orders.” (Haldimand Papers reel 21760 p. 278). One would expect a unit such as Butlers Rangers to stress good marksmanship. However, aimed fire was also frequently practiced by British regulars during the French and Indian War and American Revolution. By demonstrating this for the public, Old Fort Niagara is helping to present a more accurate picture of the activities of British soldiers in America. But don’t worry, we’re only using “squibs.” Readers can learn more about the accuracy of musket fire by visiting YouTube and watching a short video, The Effectiveness of 18 th Century Musketry, on the Old Fort Niagara Association channel. References Cuthbertson, Captain Bennett. A System for the Compleat Interior Management and Economy of a Battalion of Infantry. Dublin: Boulter Grierson, 1776. Findlay, J. T. Wolfe in Scotland in the ’45 and from 1749-1753. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1928. Haldimand Papers, Reel 21670, p. 278. Honeyman, Dr. Robert. Journal for March and April 1775. San Marino, CA: Henry E. Huntingdon Library. Houlding, J. A. Fit for Service: The Training of the British Army, 1715-95. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981. Howe/Kemble.The Kemble Papers1775-1783 v. 1. Collection of the New-York Historical Society. New York: New York Historical Society, 1883. Mackenzie, Frederick. The diary of Frederick MacKenzie. 2 vols. Cambridge Mass: Harvard university Press, 1930. Simes, Thomas. A Military Medley. London: Printed for the Author, 1777 Spring, Matthew H. With Zeal and with Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1782. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008. Tully, Mark. The Packet II. Baraboo WI: Ballindalloch Press, 2000.

Betsy Doyle: Myth or Matross? Early American history offers a range of heroines from spies to secret soldiers, yet many of their stories are poorly documented or richly embellished. Historians still debate the existence of Monmouth Courthouse’s Molly Pitcher and the motives of Manhattan’s Mrs. Murray. Until recently, another heroine, New York State’s own Betsy Doyle, remained an elusive figure from the War of 1812. According to 19 th century popular historians, Betsy or “Fanny” Doyle bravely served a cannon on the roof of Fort Niagara’s French Castle during a violent and prolonged artillery duel with British-held Fort George. Betsy reportedly carried red-hot cannonballs to a gun on the Castle’s roof, where they were immediately dispatched toward the wooden (and combustible) British stronghold. Over the years, Betsy’s legend grew, based upon an isolated account by Fort Niagara’s Colonel George McFeely that compared her actions to those of Joan of Arc. When Fort Niagara was restored between 1929 and 1934, the Daughters of 1812 placed a commemorative plaque near the site of Betsy’s heroic actions identifying her as “Fanny” Doyle. Recent research reveals that Betsy Doyle was not only a real person, but lived a harsh existence in the years following her famous November 1812 escapade. When Fort Niagara fell to British attackers in December 1813, Betsy narrowly escaped capture. With her children in tow, she fled 310 miles through a New York State winter to the United States Army’s East Greenbush Cantonment, where she fell ill with a fever. Here she remained until her premature death in 1819, brought on perhaps by a lack of pay for her services as a hospital matron.

The year 1758 marks the turning point in the French and Indian War. Until that year, there had been few British victories, while the French reaped one triumph after another. Britain’s plan for the 1758 campaign was an overwhelming assault on New France. The main thrust, with an army of 17,000 men, would be made against Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga) on Lake Champlain. Another 15,000-man force would attack Louisbourg, the fortified seaport that guarded the entrance to the St. Lawrence River. A third force of 6,000 men would march over the mountains of Pennsylvania to oust the French from the Forks of the Ohio (Pittsburgh). New France’s meager resources had to be concentrated in these three places to repel Britain’s attacks. Even so there was bitter disagreement between the two leaders charged with the defense of the colony, Governor Vaudreuil and General Montcalm. Vaudreuil conceived a plan to send General Francois Gaston, duc de Levis with 3,500 men from Montreal via Oswego to attack the Mohawk Valley. As British forces neared Ticonderoga however, this plan had to be set aside and the men moved south to bolster Montcalm’s defense of that strategic outpost. This situation left Lake Ontario only lightly defended. A small garrison of about 110 held Fort Frontenac [Kingston, ON] at the eastern end of the Lake and the newly expanded Fort Niagara housed a garrison of only about 40 soldiers. Louis Antoine de Bougainville, aide to General Montcalm commented that Niagara’s small garrison “will not even suffice to line the ramparts of one of the bastions.” [i] There was some justification for weakening the Lake Ontario district in favor of other theaters of war. Since 1756 and the fall of the British post at Oswego, the French enjoyed complete naval superiority on the Lake. Nine warships, some of French construction, others captured from the British, were available to keep the English at bay. During the summer of 1758, at least two of these ships were slated to sail between Forts Frontenac and Niagara carrying goods and supplies and bringing stone to line Niagara’s earthen walls. This situation changed dramatically on August 27 when Col. John Bradstreet, leading an army of about 3,100 British and Provincial soldiers, attacked and captured lightly defended and decrepit Fort Frontenac. In one of the boldest actions of the French and Indian War, Bradstreet’s troops captured or destroyed 60 cannons, 16 mortars, 9 sailing vessels, large quantities of military and naval stores, provisions, and Indian goods valued at 800,000 livres. Captain Thomas Sowers described the spoils of victory as, Provisions of every species for twenty thousand men for at least Six months. This fort was the grand magazine for supplying the Forts on the Lake to the Southwestward of it as well as those up on the Ohio as far as Fort Duquesne… there was scarce a Military or Naval Store which this Place did not abound with. [ii] On August 30 Governor Vaudreuil learned of Fort Frontenac’s surrender. Troops were rushed to La Presentation [Ogdensburg, NY], a fortified mission that now protected the western flank of the St. Lawrence Valley. Would the British descend the St. Lawrence to attack the heart of New France? Of equal concern was Bradstreet’s seizure of two warships anchored at Frontenac. In just a few days, the naval situation on Lake Ontario had completely changed; the initiative had passed to the British and Fort Niagara stood vulnerable. [iii] Commissary Doreil summed up the fears of many French officials when he wrote My fears are too well founded… the enemy is master of the post of Frontenac... No precaution was taken with our navy. The English, more careful than we, have burnt it, with the exception of two 20 gun brigs, which they have preserved, the more effectually to exclude us from Lake Ontario... Everything is now to be feared for Fort Niagara, which, indeed, is good, but as bare as Frontenac. [iv] Vaudreuil quickly ordered Captain Jean-Baptiste Testard de Montigny to lead 500 men in 30 canoes across Lake Ontario to Fort Niagara’s relief. If the British warships tried to interfere, Montigny’s instructions were to land and drag his canoes into the woods out of reach of the ships’ guns. Vaudreuil could scarcely have selected a more qualified commander for the mission. The 34-year-old Montigny was an expert in Indian languages and customs, had served on dozens of raids against the British frontiers, and had most recently been employed convoying supplies to Detroit. Montigny was an experienced frontier warrior equally at home in a birchbark canoe, or leading war parties of French and Indians in the woods. He gathered his forces at La Presentation and set off on or about September 11. His journey to Niagara took seven days. [v] Montigny’s arrival at Niagara about September 18 found the small garrison preparing to burn outbuildings and make the best defense they could. Niagara’s commander, Captain Jean-Baptiste Mutigny de Vassan had only learned of Frontenac’s fall a few hours before Montigny’s arrival (the news reached Niagara almost three weeks after it was received in Montreal). No doubt Montigny’s reinforcement was welcome, as was the subsequent arrival of additional convoys bringing much needed supplies. By this time, however, the danger had passed. Bradstreet’s orders did not include an attack on Fort Niagara. He had destroyed seven of the captured warships at Frontenac and had loaded the remaining two with loot from the fort. Once ashore at Oswego, Bradstreet ordered the last two ships destroyed. He returned eastward by bateau, leaving Lake Ontario in the much-weakened hands of the French. Shortly after Bradstreet’s departure from Oswego, the famous French partisan leader Jean-Baptiste Levrault de Langy arrived there and found the captured ships as well as some “barges” destroyed. His report to the Governor on September 18 allayed many fears. Later that year, the New York Gazette reported that, in view of Niagara’s weakness, it was an ‘unlucky thing’ that Bradstreet had not pressed on. It would take another year and another campaign to secure the capture of Fort Niagara. In the meantime, the British had secured two of their objectives for 1758, Louisbourg and Fort Duquesne. France retained Carillon after repulsing British forces in the bloodiest battle yet fought on American soil. As for Niagara, plans were already in preparation to reestablish a navy on Lake Ontario and to strengthen the Fort. It was agreed that Captain Pierre Pouchot should return to Niagara to replace the ineffective and haughty Vassan as commandant. Louis Antoine de Bougainville summed up the situation by writing, “Let us hope that the danger we have escaped will serve as an example to us not to abandon, in the future, a fort which is the key to the country.” [i] See Adventure in the Wilderness, the American Journals of Louis Antoine de Bougainville, 1756-60, translated and edited by Edward P. Hamilton, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman and London, 1964. pp. 283-4 [ii] Sowers to the Commissioners of Ordnance, October 1, 1758 as quoted in Royal Fort Frontenac, Dr. Richard A. Preston, and Trans. Dr. Leopold LaMontagne, ed. Toronto, Champlain Society 1958. pp. 267-8. [iii] The two vessels seized were probably the Marquise de Vaudreuil and the London. The former, mounting 16 guns, was a French schooner, built at Frontenac in 1755. The latter was a brigantine of 18 guns launched by the British at Oswego in 1756. London was captured by the French when Oswego capitulated in August 1756. See Robert Malcolmson, Warships of the Great Lakes, 1754-1834, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2001. [iv] M. Doreil to Marshall de Belle Isle, 31 August, 1758. Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New York, v. X p. 821 [v] See David A. Armour, entry for Testard de Montigny, Jean-Baptiste-Phillipe, Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online www.biographi.ca

We are grateful to Kevin Gélinas, teacher, author and historian, for providing a copy of documents from the Canadian archives, that shed light on some of the common soldiers and tradesmen at Fort Niagara in 1749. Kevin conducts ongoing research on French Canadian material culture and the fur trade. He is the author of Frontier Soldiers of New France, The French Trade Gun in North America 1662-1759 (Mowbray Publishers, 2011) as well as numerous articles on other common trade goods like axes and knives. Kevin annotated and translated the documents that serve as the basis for this article. It’s rare to get a glimpse of the lives of common soldiers and workers at Fort Niagara, especially during the French period. Several documents dating from 1749 were recently discovered in the Canadian Archives by Kevin Gélinas listing officers, common soldiers and tradesmen at Fort Niagara. The first document presumably dates from the summer of that year, because two commandants are listed; Monsieur de Raymond, Captaine Commandant and Monsieur de Beaujeu, idem commandant. In July, Beaujeu relieved de Raymond, the outgoing commandant, arriving at Fort Niagara on July 5. [i] Several other officers are listed, including Monsieur de la Perriére, lieutenant, Sieur Rouville, ensigne and Sieur de la Chauvignerie, lieutenant. Perhaps the most interesting thing about the document is the list of names of people who performed various tasks at Fort Niagara. Claude Maguille is listed as fourniture de bois (supplier of wood), Phillipe Dufay is pour ramonage de cheminés et nettoyer les armes de l’arsenal (Chimney sweep and cleaner of arms) Simon Panais is listed pour bois de chauffage (for firewood). [ii] Another page (perhaps written later) lists Au père Lajus, récollet aumônier (priest), Sieur Sermit, garde-magasin (storekeeper), Sieur Mollin, commis dans les magasins (clerk), Sieur de la Chauvignerie, interprète au dit fort (interpreter), Sieur Joncaire Chabert, autre interprète au chez les Sauvages Tsonontouans (interpreter among the Senecas). On the third page we read the names Jean Lonpré dit Sansquartier, boulanger (baker), Yves Donné, vacher (cow keeper), Pierre Lamarinne, charretier (cart driver), Jean-Baptiste Saclé dit la lime, forgeron (blacksmith) and Jean LaForge, autre forgeron employé ches les Tsanontouans (another blacksmith employed to complete work for the Senecas). The diverse number of people at the Fort continues with Pierre Charlan listed as tonnelier (barrel maker) Jean-Baptiste Charlan, second tonnelier (barrel maker), Marie Danis, ménagère (house keeper), Pierre Picard, cannonier (artillerist), Poitevin, infirmier (nurse), L’Espérance, ramoneur (chimney sweeper), Jean Chabot, charpentier (carpenter), Barthelemy Routaye, autre charpentier (another carpenter) and André Belle Isle, idem (carpenter). [iii] Captain Beaujeu’s assessment of the quality of soldiers and workers at Fort Niagara was not very high. Shortly after his arrival he wrote to Governor of New France de la Galissonniere that the garrison was “much given to drunkenness.” [iv] He found the Fort in poor condition and commented that “ I do not have a man capable of making a peg. I would be satisfied merely with men who know how to handle an axe. So, I cannot thus repair anything”… Beaujeu asked for good soldiers who were cabinetmakers, wheelwrights, masons, mowers and carpenters commenting that “these sorts of men, serving in good will, look to earn money.” [v] While on the surface, just a list of names and trades, these lists provide us with a fascinating glimpse of everyday life at Fort Niagara in the middle of the eighteenth century. [i] Beaujeu to de la Galissonniere, July 7, 1749, Le Bulletin des Recherches Historique v. XXXVII pp. 355-359. [ii] Library and Archives Canada: MG1-C11A, Volume 116 Folder 309v. [iii] Ibid. Folder 314v-315. [iv] Beaujeu to Galissonniere, July 7, 1749, , Le Bulletin des Recherches Historique v. XXXVII pp. 355-359. [v] Beaujeu to Galissonniere, August 23, 1749, , Le Bulletin des Recherches Historique v. XXXVII pp. 362-366.

Two-hundred-and-fifty-seven years ago, Fort Niagara received a famous visitor. Major Robert Rogers, a hero of the French and Indian War, arrived at the fort on June 29, 1768. Rogers had been arrested at Fort Michilimackinac the previous December and was now on his way to Montreal to be tried for treason, disobedience of orders and “lavishing away money amongst the savages.” Rogers had served as commandant at Michilimackinac since August 1766. During his tenure he loosened restrictions on the fur trade, sought the illusive Northwest Passage and hosted a grand peace council between the Sioux and Ojibwa. He also submitted a proposal to establish a civil government at the post that reported directly to the King. Over the course of his career, Rogers made some powerful enemies; among them were Sir William Johnson, Superintendent for Indian Affairs for the Northern Colonies and General Thomas Gage, British Commander-in-Chief in America. He had also alienated his secretary, Nathaniel Potter and Michilimackinac’s Indian Department Commissary, Benjamin Roberts. Potter and Roberts, neither of whom had much credibility, claimed that Rogers intended to defect to the French. Johnson and Gage, who were ill-disposed toward Rogers in the first place, chose to believe the accusations. Gage sent orders to Rogers’ second at Michilimackinac, Captain-Lieutenant Frederick Spiesmaker, to arrest him. Spiesmaker ordered Rogers into close confinement for five months and then sent him east for trial on May 21, 1768. When Rogers arrived at Niagara, he petitioned the fort’s commandant, Captain John Brown (60 th Regiment of Foot) to remove the painful leg irons he had worn since being confined at Michilimackinac. Rogers complained that the heavy irons put him in “extreme torture” rendering him lame in one leg. The irons had done so much damage, Rogers feared, “that he never will have the perfect use of his legs again.” [i] Brown ordered the post surgeon to examine Rogers and complied with Rogers’ request “least it might prejudice his health.” [ii] Brown also saw to it that Rogers had candles and supplies from a local sutler. [iii] In spite of these kindnesses, Brown was under strict orders from Gage to carefully guard the wily woods warrior while he was at Fort Niagara. Tradition has it that Rogers was lodged in the narrow center room on the second floor of the French Castle. Brown’s report to Gage only indicated that he “had a strong door and window shutters in proportion fix’d in a Room of the Stone House where there is not a fireplace, where he is lodged.” [iv] Brown ordered a sentry be posted “continually at his Door, and the same never to be opened but in the presence of a Commissioned Officer of the Sergt Major and a file of men at the door.” [v] While at Niagara, Rogers began organizing his defense. He petitioned General Gage to appoint officers to the court martial who had seen frontier service. He also lashed out at his Michilimackinac captors. He accused Captain-Lieutenant Spiesmaker of “inhumane treatment..by..keeping him four days without provisions and loading him with irons of an unlawful weight.” According to Rogers, Spiesmaker threatened to lash him to the fort’s flagpole and have him shot to death. He also accused Lieutenant John Christie of “abusive and ungentleman like language…by telling the memorialist deserved to have his tongue cut out and a Gag of iron put in his mouth, and to be chained to the floor like a dog.” [vi] He also requested Spiesmaker to send down defense witnesses and his papers. In this the Captain-Lieutenant did not fully comply. Rogers arrived at Montreal on July 17 and his trial lasted 12 days. After careful deliberation, the board of officers acquitted him of all charges. He had been arrested on the flimsiest of evidence and his accusers did everything they could to obstruct his defense. In spite of the not guilty verdict, General Gage did not grant Rogers his full freedom until almost a year later. Gage also refused to pay Rogers’ bona fide expenses while serving the Crown. This, combined with unreimbursed debts incurred during his wartime service and some risky borrowing, landed the major in debtor’s prison in 1772. Rogers had been accused of serious crimes, was jailed, tried and acquitted. Even so, his reputation was seriously damaged. The New York Mercury printed a letter from Niagara noting Rogers’ arrival at the fort and commenting that the major was believed to be “a great rascal.” [i] Gage Papers v. 79 Memorial of Major Robert Rogers, July 8, 1768. [ii] Ibid [iii] The question arises why Brown treated Rogers more kindly than his fellow officers. There is no conclusive evidence that the two had previously met, but it is true that men who had served with Rogers in the field were loyal to him. Rogers and Brown did share a common enemy- Commissary Benjamin Roberts. Roberts was described by historians as “difficult and arrogant,” and he certainly was a thorn in Captain Brown’s side when Brown served as Fort Niagara’s commandant. [iv] Gage Papers v. 78, Brown to Gage, July 1, 1768 [v] Ibid [vi] Gage Papers v. 79 Memorial of Major Robert Rogers, July 8, 1768.

Winter will soon be upon us and our thoughts will turn from travel and outdoor activities to hearth and home. Today most of us take central heating and a comfortable indoor temperature for granted. A flick of the thermostat is all that’s needed to keep warm during even the coldest days of winter. Such was not the case in early America when most depended on fireplaces, warm clothing and bedding to keep warm during the winter months. According to the Farmers’ Museum in Cooperstown, the average New York farmstead consumed about 40 cords of wood in a year. This is the equivalent of about one acre of wooded land. Translating the BTUs produced by this much wood into the cost of modern heating oil yields a heating bill of around $17,000 a year. [i] Woodcutting on the farm was the responsibility of men and boys, who spent long hard days in the woods harvesting trees for fuel. The best time to cut firewood was in the winter months when snow on the ground allowed relatively easy transport by sleigh from woodlot to dooryard . Winter was also the time when farmers had the time to lay in a store of firewood for the following year. This timetable allowed the wood to dry and season before it was needed. [ii] While cutting wood was best done during December, January and February, the arduous task of splitting and stacking was a year-round occupation. Providing firewood for a frontier military garrison intensified the challenges facing farmers. Even a reduced garrison of 30 to 40 men required a great deal of firewood for heating, cooking, baking, laundry, cleaning and hygiene. Ancillary activities like charcoal manufacture and lime burning also consumed large amounts of wood. When Captain Daniel Hyacinthe Lienard de Beaujeu assumed command of Fort Niagara in July of 1749, he lamented to New France’s Governor, Roland-Michel Barrin de La Galissonière, “There are here no more than 50 cords of wood of the 1,200 which are consumed annually.” [iii] That means, by Beaujeu’s estimate, the Fort consumed about 30 acres of trees each year when its footprint was still relatively small. After the British captured the Fort, Major William Walters of the 60 th Regiment of Foot wrote to General Amherst “I keep the Troops constantly employed of fetching wood for the Garrison on sleighs which is good Exercise and adds greatly to their Health , as long as the frost and snow continues.” [iv] Walters continued to gather firewood through the year, writing in August 1762 that he had issued orders “… to have the garrison … supplied with wood … ” [v] By November of 1762 General Amherst wrote to Major John Wilkins, who had replaced Walters as commandant: Before I received your letter, Lt. Col. Eyre had shown me a copy of Lt. Demler’s report which satisfied me that the troops at Niagara had been usefully employed during the summer; but I am now to express my particular approbation of the measures which I see you had taken to preserve the health of your garrison by establishing a brewery whereby the men should be supplied with spruce beer at the easy rate of one copper a quart; and likewise of the precautions to lay in a stock of firewood, and the regulations you had made for each Mess being supplied with plenty of vegetables from their own gardens, all which must make the men live comfortably during the winter and consequently be the more fit for service when the weather will permit their being employed. [vi] Five years later, in 1767, we find another reference to firewood in a letter from Captain Alexander Grant of the Naval Department to Booty Graves at Niagara: You are hereby ordered and directed to take on you the command and direction of the Naval Department at Niagara, taking care to follow all orders and directions that you shall receive from time to time from Captain Brown, the commanding officer at Niagara, or myself; & all officers and seamen of the above Department are to obey you as such... firewood must be procured for Mr. McTavish in his room all winter…. You’ll always have sufficient of firewood for the people ... [vii] One of the difficulties in gathering wood resulted from the long-term military occupation of the site. Defense considerations meant that no trees stood close to the Fort. With the garrison’s voracious appetite for firewood, supplies quickly moved ever farther from the Fort’s walls. One solution to this problem was to use watercraft to move wood. On November 2, 1774 Fort Niagara’s new commandant, Lt. Col. John Caldwell, wrote to General Gage, asking for bateau to move wood from sources along the Lake Ontario shore: I must observe that the scow when built will be so unwieldy and draw so much water that she can only be made use of on the river, for one Gale of Wind upon the Lake (from the shores of which we get our best and nearest wood) would infallibly destroy her. [viii] Harvesting firewood could also be dangerous. In January 1814, shortly after they captured Fort Niagara from the United States, British troops left the Fort on a mission to gather firewood. After covering only about one-half mile of ground, the woodcutting party was attacked by American troops, suffering several casualties. American Major General Amos Hall reported to New York Governor Tompkins on January 13, 1814: On the 8 th inst. a detachment under the Command of General John Swift (a volunteer) and Lieut. Colonel C. Hopkins, with about 70 men, surprised a party of the British who were procuring wood about half a mile from the Fort, fired upon them, killed four of the enemy, lost one of their own men, and took eight prisoners, subsequent to which a large force of the enemy was observed to be in motion, which induced our troops on that station to fall back 4 or 5 miles to a more defensible position. The affair ended here and all is quiet . [ix] A British account of the same incident appeared in a letter from Lt. General Gordon Drummond to Sir George Prevost: I am concerned to report to Your Excellency a circumstance of an unpleasant nature which occurred at Fort Niagara which..may be principally attributed to the want of exertion, or…to the neglect of the commissariat in not throwing a supply of that indispensably necessary article, fuel, into that place. A party was sent out on the morning of the 9 th to cut wood, under protection of a sergeant’s covering party, was attacked by a body of the enemy, reported to consist of about 150 men, and driven in. The sergeant was severely wounded and nine men of the working party, is supposed, taken prisoners…it appears very extraordinary that any individuals of so small a fatigue party should not have been able to affect their escape, and particularly as it appears they were not furnished with arms to assist the covering party in repelling the attack or in effecting a slow and cautious retreat. [x] Thus gathering firewood could be a mundane, arduous and even dangerous task, but one that was never far from the minds of Fort Niagara’s winter garrisons. [i] The Farmers’ Museum: Cutting Firewood: Preparing for Winter, Part 2. http://thefarmersmuseum.blogspot.com/2010/cutting-firewood-preparing-for-winter.html . Fireplaces were only about 10% efficient, with most of the heat going up the chimney. Stoves came into use during the 18 th century but for most, the fireplace was still the most common form of heating. Peter Kalm, visiting New France in 1749 noted stoves in use, including military installations in Quebec. [ii] See Nylander, Jane C. Our Own Snug Fireside: Images of the New England Home 1760-1860. 1993 Alfred Knopf, NY pp. 82-84. [iii] Beaujeu to de la Galissoniere, July 7, 1749. [iv] Walters to Amherst. Feb 2. 1761 Amherst Papers v. 21 [v] Walters to Amherst. Aug. 19, 1762 Amherst Papers v. 22 [vi] Amherst to Wilkins, November 28, 1762, Amherst Papers [vii] Grant to Graves, Oct 23, 1767 Haldimand Papers 21678. McTavish was Simon McTavish, possibly a clerk for the Naval Department at Niagara. [viii] Caldwell to Gage, November 2, 1774, Gage Papers, v. 124. [ix] Major General Hall to Governor Tompkins, January 13, 1814. Documentary History of the Campaigns Upon the Niagara Frontier 1812-1814. Lundy’s Lane Historical Society, Lt. Col. E. Cruikshank, ed. v. IX p. 111. General John Swift had an interesting military career. He was born in Connecticut in 1761 and served as a private in Elmore’s Regiment during the American Revolution. Following the Revolution, he founded the town of Palmyra, NY. He reentered service at the outbreak of the War of 1812. After leading the attack on the woodcutting party outside Fort Niagara, he took part in the 1814 campaign in Canada and was killed near Fort George July 12, 1814 [x] Ibid, p. 131.

As America approaches its 250 th birthday in 2026, attention turns toward the era of the American Revolution and the founding of the United States. New York State has created a 250 th Commemoration Commission https://www.nysm.nysed.gov/revolutionaryny250 that has identified the period of 2024 to 2033 as the era of commemoration. Locally, the Niagara County Legislature has created a Niagara County USA 250 Committee whose mission is to garner interest in Niagara County’s history among county residents, to strengthen Niagara County’s status as a heritage tourism destination, to foster stewardship of historic and cultural resources in the county and to build community pride among a diverse population. As the era of commemoration begins, we look back at the year 1774, the year before the outbreak of the American Revolution. While open combat did not occur until 1775, many historians consider 1774 to be the year the Revolution began “in the hearts and minds of the people.” Important events of the year include passage of the Coercive Acts (to punish Boston for the Boston Tea Party), the Quebec Act ( which expanded the province of Quebec’s territory to include much of what is now southern Ontario, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, and parts of Minnesota), and the meeting of the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Although Fort Niagara was far removed from most of these events, 1774 was also an eventful year for the fort. On August 7, 1774, His Majesty’s Eighth (King’s) Regiment of Foot relieved the Tenth Regiment as the garrison of Fort Niagara. This marked the beginning of a long association of the Eighth with the post, the Niagara Frontier and the Great Lakes region. It would be eleven years before the Eighth would be relieved and sent home to England. The Eighth Regiment thereby became Fort Niagara’s longest serving British infantry unit. The Regiment had been in North America since 1768, garrisoning Quebec and other lesser posts in the St. Lawrence Valley. Early in 1774, the Eighth was ordered to prepare to move up the St. Lawrence to take over British posts in the upper country. The regiment moved southwestward in two divisions, sailing in bateaus full of officers, men, women, children and baggage. The lead division, destined to garrison the posts farthest away, left Lachine, just west of Montreal, the third week of May. Three companies would garrison Detroit and two would occupy Fort Michilimackinac. The second division, under the regiment’s commander, Lt. Col. John Caldwell, embarked in early June. On June 17, the second division reached Oswegatchie, where the regiment’s light infantry company would be posted. Delayed by contrary winds, the remainder of the second division did not reach Niagara until the first week in August. Lt. Colonel Caldwell took command of the fort on August 7, relieving the Tenth Regiment of Foot, a unit that had served at the fort since 1772. With Caldwell were the four remaining companies of the regiment, about 200 soldiers. Half a company would be dispatched to garrison Fort Erie, leaving a force of only 3 ½ companies to man Niagara’s massive yet deteriorating defenses. Yet, not all was quiet on the western front. As the Eighth moved west, hostilities broke out between Virginia frontiersmen and Shawnee and Mingo warriors in the Ohio Valley. This bloody frontier conflict, known as Lord Dunmore’s War lasted until October 1774. In July, while trying to ameliorate the situation, Sir William Johnson suddenly died, leaving a huge void in British/Native diplomatic relations. (Learn more about Dunmore’s War at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=psJ1Hgybfec ) British officials were concerned that the warring nations would enlist the support of the Haudenosaunee. Lt. Colonel Caldwell gathered intelligence from local traders and friendly Seneca. He reported to his superior, General Thomas Gage that he had “spared neither trouble nor expense to find out the part the Six Nations were likely to take in these disputes.” Caldwell convened many meetings with local Senecas trying to impress them with British strength. He told them he “was sent to Niagara in the character of Sachem as well as warrior.” If the Six Nations remained quiet, the British would remain their friends, if not, consequences would be severe. In the end, the Six Nations refused the hatchet and remained at peace. The Eighth reached Fort Niagara during the final year of peace before the Battles of Lexington and Concord set the American Revolution in motion in April 1775. At first, most of the soldiers’ time would be taken up by the normal routine of maintaining a decaying frontier fortress. Caldwell and his troops had many tasks to perform to maintain their buildings and walls and to provide firewood and supplies for the garrison. The outbreak of war, however, meant that the regiment would soon have a much more active military role.

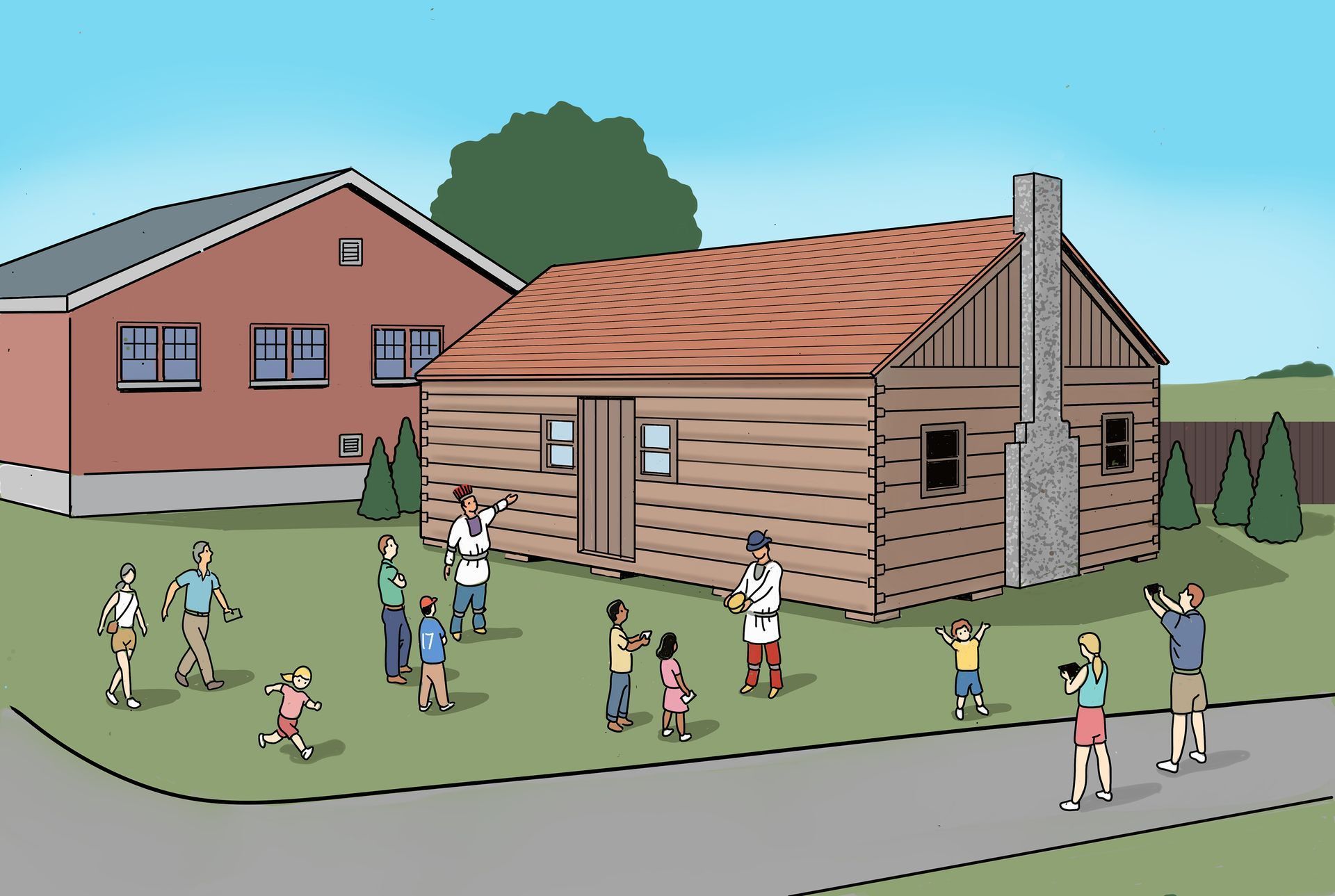

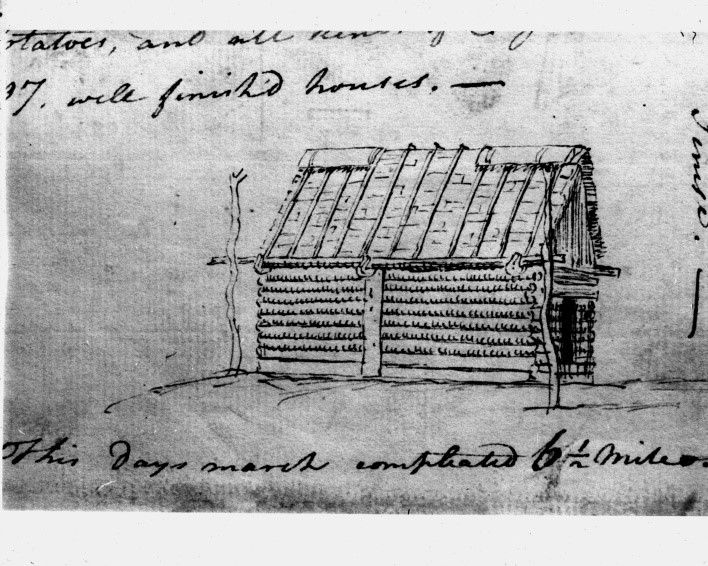

Old Fort Niagara Launches Campaign for Native American Education Center Old Fort Niagara has always stood as a place where stories converge—military triumphs, global conflicts, and enduring alliances. But some of the most powerful stories are those that haven’t always been told in full. Today, we’re taking a big step to change that. As part of our efforts to commemorate the upcoming 250th anniversary of the American Revolution, we’re proud to announce the creation of a Native American Education Center —a new space that honors the deep and ongoing connection between Old Fort Niagara and the region’s Indigenous nations. This hewn-log structure, modeled after 18th-century Native dwellings built near the Fort during the Revolutionary War, will become a powerful, living classroom. During the Revolution, thousands of Native people—many allied with the British—sought safety at Fort Niagara. Temporary shelters were erected just outside the Fort’s walls. The new Education Center will reflect these historic homes, offering visitors an immersive way to explore the past through Native perspectives. A Space for Storytelling, Teaching, and Tradition Inside the center, visitors will discover sleeping, dining, and storage areas, complete with period-authentic trade goods, clothing, tools, and more. But more than artifacts, it will be the voices that bring this space to life. Led by Native interpreters, the Center will offer deeper insight into Native history and culture, the complexities of military alliances, diplomacy, and survival during wartime. As Jordan Smith (Mohawk, Bear Clan and Head of Native Education at the Fort) shares, this programming is about more than the past—it’s about connection: “This facility and our enhanced Native programming will undoubtedly enrich the experience of thousands of school students, area residents, and visitors, who will have the opportunity to engage fully in both the military history of the Fort and its Native history.” In addition to its role in daily interpretation, the building will host workshops on traditional skills like moccasin making, quillwork, beadwork, and Native languages. It will also serve as a gathering space for small group events and cultural meetings—supporting ongoing cultural continuity and community connection. Help Us Build It The Fort has already raised $200,000 toward the project, but we need your help to finish strong. Our public fundraising campaign —co-chaired by Chief Brennen Ferguson (Tuscarora, Turtle Clan) and Michael McInerney (retired CEO of Modern Disposal Services, Inc.)—is underway, with a goal to raise an additional $50,000 by early September. Chief Ferguson, speaking at our campaign kickoff event, reflected on the meaning of this project: “This cabin will stand not only as a window into the past, but as a doorway to greater understanding. Native Nations lived, traveled, and governed here long before European arrival. This structure will support the efforts of Native staff at the Fort and help share a fuller story—one that honors the presence, contributions, and strength of Indigenous Peoples.” McInerney added that the project also supports Old Fort Niagara’s long-term sustainability: “The Native American Education Center will draw new visitors and school groups, helping Old Fort Niagara broaden its reach and remain a vibrant educational resource for generations to come.” Be Part of the Story The new Native American Education Center will be located just outside the Old Fort Niagara Visitor Center, with a planned opening in spring 2026 . It will be open during regular hours and available for special evening programs lit by traditional lighting. We invite you to be part of this meaningful project. Whether you’re passionate about history, education, or cultural preservation, your support helps us build something lasting—something that reflects the full story of this land. Visit our GoFundMe page to give or learn more. Every contribution brings us closer to opening the doors.

Magasin a Poudre/Institute d' Honneur Visitors who enter Old Fort Niagara through the South Redoubt are first impressed with the French Castle, standing on the far side of the parade ground. Less noticed perhaps is the tall, almost windowless building to the left; the Powder Magazine. Erected in 1757, at the high water mark of French fortunes during the French and Indian War, the magazine today reminds us of France's far-flung North American empire at its zenith. It also stands as a monument to its designer, Captain Pierre Pouchot who created a structure that survived a desperate siege and was used for ammunition storage into the twentieth century. Powder magazines may not be the most interesting of structures, until something goes wrong. History is full of accounts of gunpowder supplies exploding with disastrous consequences. One of the earliest recorded incidents of accidental explosion occurred in 1280 when Mongols blew up a Chinese arsenal through carelessness. Erasmus described a devastating explosion in Basel, Switzerland in the early 16 th century and a powder supply in Delft, Holland exploded on October 12, 1654 destroying much of the city. In this last incident, about 40 tons of powder, stored in a magazine that formerly served as a Clarissen convent, blew up when the magazine's keeper, Cornelis Soetens, opened the door of the magazine to check a sample of the powder. Over a hundred people were killed and thousands injured. Luckily, many of the city's residents were away from home. The damage was portrayed by the artist Egbert van der Poel in his painting A View of Delft After the Explosion of 1654. The stakes were indeed high; one spark could wreck a fortress or town and kill half of its inhabitants. During late medieval times, gunpowder was often stored in towers located along a castle's outer perimeter. As the capabilities of artillery improved, the folly of this practice became obvious. During the sixteenth century, military engineers began to design specialized buildings to store gunpowder. These designs were gradually improved and somewhat standardized by the 18 th century. The safest place for a powder magazine was underground, in a chamber roofed with heavy beams and covered with a deep layer of earth. Mortar bombs and other incoming fire would spend itself harmlessly in the dirt and the garrison would live to fight another day. Most forts built in North America featured just this kind of magazine. 1 The disadvantage of underground magazines was dampness. Gunpowder that drew damp became little more than a useless sooty black paste. Above-ground storage was certainly a better option for keeping the powder dry, but such magazines were much more exposed to enemy fire. To compensate, they had to be built with thick stone walls, and arched ceilings to render them bombproof. During the seventeenth century, the preeminent military engineer of the age, Sebastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707) standardized magazine design in France. Vauban's designs were single-story stone buildings with thick walls, stone arched ceilings that were designed to withstand artillery fire, steep gabled roofs, and buttresses that strengthened the arch. Inside the building, raised wooden floors and wood-lined walls helped keep out the damp. Often, crushed stone or chips underlay the floor, further promoting a dry atmosphere. Perforated iron plates and masonry dice (baffles), set into the walls, allowed air into the magazine without exposing the building's contents to flying embers or sparks. Vauban's magazines were designed to house 45-60 tons of gunpowder. Examples of Vauban's work can be seen at Gravelines near Dunkirk, at Fort Barraux, near Grenoble, and on the Crozon Peninsula in Brittany. 2 Vauban's designs provided a valuable starting point for Captain Pierre Pouchot as he set out during the winter of 1756-57 to construct a new powder magazine at Fort Niagara. Pouchot had spent the winter of 1755 and the first half of 1756 at Fort Niagara erecting temporary barracks and constructing massive earthworks designed to withstand artillery fire. From this time he undoubtedly realized that the existing magazine at the west end of the French Castle was far too small to house the powder supply an expanded fort would need. After a brief sojourn at the siege of Oswego (see the March 2006 issue of Fortress Niagara), and a road building assignment at La Prairie, Pouchot returned to Fort Niagara in October 1756 to complete the transformation of the post. This time he was placed in command of the Fort, a post that had previously been reserved for officers of the colonial regulars (compagnies franches de la Marine), not regular army officers from France. On his journey to Niagara, he was accompanied by soldiers from three army regiments, his own Bearn Regiment, the Guienne Regiment, and the La Sarre Regiment. Pouchot sited his new powder magazine at the southern end of the enlarged fort, next to a newly built provisions storehouse. To make room for the magazine, he tore down a temporary barracks that had been constructed the year before. Pouchot probably imported the stone for the magazine from Cataraqui (Fort Frontenac) where modern Kingston, Ontario stands today. The stone was transported across Lake Ontario aboard a fleet of sailing vessels that France maintained on Lake Ontario. In addition to the magazine, Pouchot superintended the construction of new log barracks, storehouses, a forge, stable, hospital and church. In January 1757 he dispatched a report to the Marquis de Montcalm reporting progress on these buildings. Bitter cold however, retarded the work. Construction continued through the spring and summer months, and as of May, Montcalm recorded that the magazine at Fort Niagara was not yet finished. During this time, Pouchot had more on his mind than construction. Relations with Native allies from the Great Lakes and Midwest consumed much of his time as hundreds of warriors gathered at Niagara. Some came to form war parties to attack English settlements to the south, while others passed through on their way east to join the French Army in an attack on British Fort William Henry on Lake George. News of French victories the previous year had traveled fast and Ottawas, Ojibwas, Menominees, Potawatamies, Winnebagoes, Fox, Sauk, Miami, and even Iowa warriors now made their way to Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga) where the French Army assembled for its descent on Fort William Henry. Here, nearly 2,000 Native warriors gathered to support the French. Rumors that victors would be “swimming in brandy” and that Montcalm was willing to ransom prisoners motivated Native warriors to travel as far as 1,500 miles to participate in the battle. In all, 33 nations were represented, the largest assemblage of Native warriors ever to take the field to support the French cause. Many of the warriors traveling through Niagara from the west left their women and children at the Fort to be cared for while they took the field. 3 By September, 1757, Pouchot could report that Fort Niagara and its buildings were finished and its covered ways stockaded. His task completed, Pouchot was relieved of his command in October 1757. In his memoirs he wrote “Since this fort was a very considerable one, because of its position and the large number of Indians who had dealings there and came from all parts to trade and form war parties, it was soon coveted by all of the officers of the colony.” 4 Pouchot was relieved by Captain Jean Francois de Vassan of the colonial regular troops. The magazine Pouchot left behind was one of the largest in the colony, designed to hold up to 50 tons of gunpowder. The building's four-foot thick stone walls, earth covered arched ceiling, and steep gabled roof is strikingly similar to Vauban's standard designs that graced fortresses throughout France. Conspicuously missing from Pouchot's magazine, however, were the massive stone buttresses that Vauban used to strengthen the arched ceilings of his magazines. Whether these were omitted as a frontier expedient or through inexperience is not known. Regardless, Pouchot left the Fort with a substantial above-ground powder magazine that was capable of withstanding the artillery that British forces were likely to drag and float west from the Mohawk Valley. Inside the building, wooden racks extended from floor to ceiling, holding hundreds of powder casks, each of about 50 pounds capacity. In all, about fifty tons of gunpowder could be safely stored until needed. Ironically, much of the powder stored in the magazine during the final years of French occupation may have been British in origin, captured from General Edward Braddock or at the fall of Forts Oswego and William Henry. The question arises, why such a large magazine? The answer lies in the Fort's own need for a large powder supply and its role as a supply depot for other French posts in the upper Great Lakes and the Ohio Valley. By 1757 Fort Niagara was well armed with 30 pieces of artillery including twelve 12-pounders according to Captain Francois Marc-Antoine Le Mercier, commandant of artillery in New France. 5 In the event of a protracted siege, a large powder supply would be necessary, as subsequent events were to demonstrate. Fort Niagara also forwarded powder supplies to posts in the upper Great Lakes and in the Ohio Valley. A good supply of gunpowder was especially important at Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh) not only to defend the Fort itself, but also to supply the numerous native warriors that frequented the post. In addition to some 250 soldiers, Fort Duquesne at times hosted up to 500 Native allies who carried out raids on the frontiers of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. During the course of the war, these raiding parties killed approximately 1,500 settlers, carried off 1,000 more as prisoners and drove even more from their homes. 6 To keep these warriors in the field, it was necessary to provide supplies, including gunpowder, most of which had to come through Fort Niagara. As Governor Vaudreuil explained in 1758: ...tis impossible to avoid the consumption of powder in war...there is no country where so much of it is consumed, both for hunting and distribution among the Indians; burning of powder is equally a passion among the Canadians, but I think we gain thereby in the day of battle, by the correctness of their aim in firing. 7 Fort Niagara's powder magazine's greatest test came two years after its construction when it endured the siege of 1759. Not only did the structure survive a week long bombardment by British artillery, it saw service disbursing an estimated 24 tons of powder in defense of the Fort. 8 A British inventory taken after the Fort's capture revealed that 15,000 pounds of bulk powder remained. Prior to surrendering the Fort, French officers were said to have locked personal valuables in the magazine to prevent their theft. 9 As the years passed a few changes were made to the building. Prior to the American Revolution, the British added a small entryway that survives today and added buttresses to the building exterior. These were removed in the mid-19 th century when windows and ventilation slits were also added. The building remained sound for ammunition storage into the twentieth century; as late as World War One, the United States Army stored ammunition in Pouchot's magazine. Perhaps the most infamous story surrounding the magazine is the incarceration there of William Morgan, an early nineteenth-century anti-Masonic activist. Morgan was imprisoned in the magazine just before his mysterious disappearance in 1826. Following its restoration between 1932 and 1934, the powder magazine served as an exhibit building, containing orientation exhibits. Restoration of the building was made possible through the generosity of Wallace I. Keep and the building was dedicated as L' Institut d' Honneur on October 5, 1935. Ironically, the plaque dedicating the building lists its builder as Captaine Francois Pouchot. With the opening of the Visitor Center in 2006, the building interior was cleared of exhibits and will be restored in 2007 to its 18 th century appearance through a special projects grant from the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. Used as ammunition storage, a vault for valuables, a prison, and an exhibit gallery, the powder magazine's changing usefulness has allowed it to survive where many others have crumbled. Notes: 1 Travelers wishing to visit an underground magazine from this period can tour one at Fort Ligonier in Ligonier Pennsylvania. Photographs and drawings of this structure can be found in Charles Morse Stotz, Outposts of the War for Empire, (Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, 2005) pp 172-175. 2 See Christopher Duffy, Fire and Stone: The Science of Fortress Warfare, 1660-1860 (Greenhill Books, London 1996) pp. 91-92. See also Paddy Griffith, The Vauban Fortifications of France (Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2006). 3 See Ian Steele, Betrayals: Fort William Henry and the “Massacre” (Oxford University Press, 1990). 4 Pierre Pouchot Memoirs on the Late War In North America Between France and England, Brian Dunnigan, ed.(Old Fort Niagara Association Youngstown, NY 2004) p. 133 5 E. B. O'Callaghan ed. Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New York : (15 vols.: Albany, 1856-1877), X, p. 656 6 See Matthew C. Ward, Breaking the Backcountry: The Seven Years War in Virginia and Pennsylvania. 1754-1765. (University of Pittsburgh Press 2003). 7 M. de Vaudreuil to M. de Massiac, Nov. 1, 1758. DRCHSNY v. X p. 863 . 8 Pouchot, Memoirs p. 237 9 Brian Leigh Dunnigan Siege-1759 The Campaign Against Niagara, (Old Fort Niagara Association, Youngstown, NY 1996) p. 106

After an absence of over 17 months, American troops re-occupied Fort Niagara on May 22, 1815. The Fort had been lost on the morning of December 19, 1813, and a British garrison occupied the post well past the cessation of hostilities at the close of the War of 1812. According to the Treaty of Ghent, signed on December 24, 1814 and ratified by the United States Senate on February 16, 1815, “all territory, places, and possessions whatsoever, taken by either party from the other…shall be restored without delay.” In the case of Fort Niagara, the reoccupation can be described as “protracted” rather than “without delay.” The Buffalo Gazette was one of the first papers to report the American repatriation. On May 23, 1815 the Gazette reported: Yesterday Fort Niagara was evacuated by the English and taken possession of by American troops. This event has been protracted to an unreasonable length, but we understand it is to be explained in this way: Major General Murray, [provisional Lt.] Governor of Upper Canada, sent a dispatch to Sacketts Harbor in April last, for Major General Brown, notifying the general that he was authorized and ready to deliver up Fort Niagara, according to treaty. This dispatch reached the harbor a few days after General Brown left that place for Washington. Mails now pass to Lewiston and will shortly be extended to the fort. Captain Craig of the artillery is assigned to the command of Fort Niagara. [i] Captain Craig’s 60-man detachment marched from Buffalo on May 21 and took possession of Fort Niagara at about 11:00 a.m. the next day. The Fort’s British garrison was prepared to hand over the Fort. In addition to writing to Brown, Murray notified British Major General de Watteville at Fort George of the impending transfer. [ii] Captain Henry K. Craig, was born at Fort Pitt, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on March 7, 1791. He was educated at Pittsburgh and just after turning 21, was commissioned a lieutenant in the 2 nd U.S. Artillery. He fought at the capture of Fort George in May 1813 and at Stoney Creek in June. He advanced to Captain in December 1813 and in the spring of 1815, drew the assignment to reoccupy Fort Niagara. Henry K. Craig came by his military profession honestly as both parents had strong connections with the American army during the Revolution. Craig’s father, Isaac, was a distinguished artilleryman who had seen extensive service during the American Revolution. Isaac was born near Hillsborough in County Down Ireland in 1741 or 1742 (sources disagree). He was trained as a carpenter, but left Ireland for Philadelphia in the 1760s. When the American Revolution broke out in 1775, Isaac Craig received a State commission as Captain of Marines. In the closing days of 1776, he crossed the Delaware with Washington and fought in the battles of Trenton and Princeton. Isaac Craig joined the 4 th Continental Artillery Regiment in 1777 and fought at Brandywine and Germantown. He endured the difficult winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge and was then posted to the Washingtonburg laboratory at Carlisle, Pennsylvania to learn the art of ammunition preparation. In 1779 he accompanied the Sullivan-Clinton campaign into the country of the Six Nations. Isaac’s life changed in 1780 when he was ordered west of the Allegheny Mountains to support George Rogers Clark’s projected campaign against Detroit. Posted to Fort Pitt, Craig assisted Clark in preparing his expedition, then accompanied Clark to the falls of the Ohio. Craig returned to Fort Pitt when the expedition was cancelled due to lack of manpower and the decisive defeat of the expedition’s rearguard in August 1781 (by no less than Joseph Brant). From then on, except for brief periods, Isaac Craig remained in Pittsburgh for the rest of his life becoming a prominent merchant in the fledgling community. In 1791, about the time Henry was born, Isaac was appointed Deputy Quartermaster and Military Storekeeper at Pittsburgh. [iii] Henry Craig’s mother Amelia, also came from a military family. Her father was General John Neville who fought in the French and Indian War, Dunmore’s War and took command of Fort Pitt early in the Revolution. Still in Pittsburgh, Neville played a prominent role on the government side of the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. Considering his parents’ background, it is little wonder that son Henry was named Henry Knox Craig after his father’s friend, Henry Knox, the former Continental Army chief of artillery and, in 1791, President Washington’s Secretary of War. Henry Knox Craig’s tenure at Fort Niagara did not last long, as Captain William Gates of the Corps of Artillery was ordered here in July 1815. In fact, five days before he marched to Fort Niagara, Craig was officially transferred to the light artillery. At 24 Craig still had a long career ahead of him. During the 1820’s he supervised lead mining operations in Missouri and Illinois and was promoted to major in 1832. Prior to the Mexican War he was assigned to the Ordnance Corps and served as Chief of Ordnance for General Zachary Taylor. Craig distinguished himself at the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma in May 1846 and was later brevetted Lt. Col. for “gallant and meritorious conduct.” Following the Mexican War, he served as inspector of arsenals from 1848 to 1851 then was appointed Chief of Ordnance with the rank of Colonel. The 1850s was a decade of retrenchment for the Army and Craig did his best to seek adequate funding for weaponry and munitions. He kept pace with developments in other countries and encouraged the testing of breech loading muskets as well as modified 12-pounder cannon. According to the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps, Craig was “regarded as an experienced, conscientious, and dedicated officer, although he held strong views and was sometimes acerbic with his subordinates.” [iv] With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Secretary of War Simon Cameron relieved the 70-year-old Craig of his duties, replacing him with “more vigorous leadership.” Craig took the matter of his replacement to President Lincoln but the commander-in-chief declined to intervene. About this same time, Craig’s youngest son, Lt. Presley Oldham Craig, who had also joined the artillery, was killed at the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861. Craig served another two years in an advisory capacity and finally retired in June 1863 after almost 50 years of military service. He died in Washington D.C. in 1869. [i] Buffalo Gazette, May 23, 1815 [ii] Major General Louis de Watteville to General Sir George Murray, May 23, 1815 [iii] See Papers of the War Department 1784-1800, http://wardepartmentpapers.org/blog/?p=1145 and John Trussell, The Pennsylvania Line, Regimental Organization and Operations, 1775-1783. pp.197-198. [iv] Colonel Henry K. Craig, Chief of Ordnance, 1851-1861, U.S. Army Ordnance Corps. www.goordnance.army.mil/history/chiefs/craig.html

Major George Armistead's name is indelibly linked with America's most famous flag; the Star Spangled Banner. What is more obscure is his connection with another preserved flag from the War of 1812 that currently hangs at Old Fort Niagara. Armistead was born in Caroline County, Virginia in 1780. He came from a military family and entered the United States Army in 1799 as an ensign. From 1801 to 1806 Armistead served as First Lieutenant and Assistant Military Agent at Fort Niagara. He arrived at the Fort September 1, 1801, assigned to Captain James Reid's Company, Second Regiment of Artillerists and Engineers. Throughout his career, Armistead liked big flags. Shortly after he arrived at Fort Niagara he discovered that the post had no national colors. The US had taken over Fort Niagara from the British in 1796. On August 11 of that year, American soldiers raised the new 15-star, 15-stripe flag on the garrison flagstaff located in the north bastion. Recently-landed six pounders roared out a 15-gun salute. Apparently these colors were not longer present in 1802, prompting Armistead to request the purchase of a 48-foot by 38 foot banner. This flag was of the pattern established by Congress in flag legislation of 1795 including one star and one stripe for each state in the Union. Armistead did not care for Fort Niagara's harsh winters and took extended furloughs during the winter months to visit relatives in Dumfries, VA. In 1806 Armistead was assigned to the Arkansas Territory and then in 1809 was promoted to Captain and transferred to Fort McHenry on the Patapsco River in Baltimore. He returned to Fort Niagara in the Spring of 1813 as a Major in the 3rd Regiment of Artillery. During his short stay at Fort Niagara, he almost certainly saw another garrison color flying over the Fort. This one, measured at least 22 by 28 feet, a little smaller than the 48' by 38' foot flag requested by Armistead in 1802. At Fort Niagara, on May 27, 1813, Armistead distinguished himself at the bombardment and capture of Fort George, a British-held post across the river in Canada.. General Henry Dearborn reported to the Secretary of War “I am greatly indebted to Colonel Porter, Major Armistead and Captain Totten for their judicious arrangements and skillful execution in demolishing the enemies fort and batteries, and to the officers of the artillery.” For his distinguished service, Armistead was given the honor of carrying British battle flags captured in the fall of Fort George to Washington for presentation to President Madison. On June 27, 1813, while in Washington, Armistead received orders to take command of Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor. Shortly after his arrival he wrote, “We, sir, are ready at Fort McHenry to defend Baltimore against invading by the enemy. That is to say, we are ready except we have no suitable ensign to display over the Fort, and it is my desire to have a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance.” As a result, what we call today the Star Spangled Banner was made under government contract in the summer of 1813 by professional flag maker Mary Pickergill and members of her family. The flag measured 30 feet by 42 feet. During the Battle of Baltimore September 12-14, 1814, British ships bombarded Fort McHenry for 25 hours. When Armistead's flag of defiance appeared at dawn, showing that the Americans still possessed the fortress that blocked British ships from Baltimore Harbor, Francis Scott Key was prompted to write “The Star Spangled Banner” a poem that was eventually set to music and became our national anthem. Armistead was soon promoted by President Madison to the rank of Lt. Colonel and given possession of the garrison flag. The Banner remained in the family's possession until turned over to the Smithsonian Institution in 1907. He remained in command of Fort McHenry until his death in 1818. Ironically that same year, new flag legislation made 15-star, 15 stripe flags obsolete. What of the Fort Niagara flag, the banner that Armistead no doubt saw just before leaving for Washington and his new assignment as commandant of Fort McHenry? On the night of December 18-19 1813, a 562-man British force crossed the Niagara River and captured Fort Niagara and the garrison flag. The captured flag was sent to London where it was laid at the feet of His Royal Highness, the Prince Regent, later King George IV. Soon after it was sent to the home of Sir Gordon Drummond, commander of British forces in upper Canada. Here it remained and was damaged by fire in 1969. In the early 1990s the Old Fort Niagara Association purchased the flag and returned it to western New York. For the first time in 2006, it was placed on permanent public display in a new Visitor Center. The Fort Niagara flag is an older sister the more famous Star Spangled Banner. It is one of only about 20 known surviving examples of the Stars and Stripes dating before 1815 and is one of the best documented of these early flags. The Fort Niagara War of 1812 flag and its more famous sister, the Star Spangled Banner, are linked through the personage of Major George Armistead, a brave officer who stood in defense of his country on more than one occasion.

Beginning in the fall of 1778, there are several references to the construction of housing for Loyalist and Native refugees. The Fort’s commandant, Col. Mason Bolton, insisted that billeting inside the Fort be reserved for regular troops. As Col. Butler’s Corps of Rangers returned to Niagara after the 1778 campaign, the need to construct housing for them became acute. Initially, the rangers were issued tents, but this proved inadequate for sheltering the men against Niagara’s winter weather. In July, Governor General Frederick Haldimand, who was stationed in Quebec, wrote to Bolton: I send him (Captain Robert Matthews) up to you…and as your garrison will be reinforced in autumn, he may be employed in erecting such additional log houses as may be necessary for their (the rangers’) lodging. Construction of the Ranger barracks was originally begun on the Bottoms below the Fort. This site proved unsatisfactory as represented in this letter from Walter Butler: On Captain Butler’s arrival from Canada the latter of August 78 (Major Butler having arrived but a few days before from the Indian Country in a very ill state of health) he found a Barrack in building and the frame nearly ready to be put up, which Col. Bolton told him was to be a Barrack for the Rangers: on finding the place very ill situated for quarters whether for officers or men and out of the Fort, in the Bottom, where in Fall and Spring there is half a leg deep of water and mud, and not more ground than to erect one Barrack which was not sufficient Quarters for the officers: and even were there ground sufficient such a situation no officer could be answerable for his Men: In justice to the service from the place being open to Indians day and night, and they constantly drinking, and often very troublesome, whence unhappy consequences might arrive, from such a number of men mixt with them: For those reasons Captain Butler waited on Major Butler, and tho he was very sick, represented those matters to him. Finally the decision was made to move the rangers to the west side of the Niagara River. In November, Bolton wrote to Haldimand, Major Butler is building Barracks for the Rangers on the opposite side of the river and Captain Matthews is employed in cutting a strong log house (which will contain 40 or 50 men) at the Upper Landing and we are also at work with the additional Log Houses for this Garrison agreeable to Your Excellency’s orders. In addition to these log barracks, Col. Bolton refers specifically to log houses for Native families at the Bottoms. On November 11, 1778, Bolton wrote: On Niagara side not having boards for officer floors and if Capt. Butler were not greatly mistaken, the artificers employed in repairing said barracks and putting in order the log houses in the bottom for several Indian families were paid in the Ranger Barracks acct. The tents of the Rangers going into barracks were given to a number of the Indians who came in to Receive his Majesty’s Bounty to cover them from the weather and have never been returned.